A Flourish of Sound: Esbjörn Svensson's Alternating Pedal Points

A piano teacher of mine once theorized that sound waves produced by Chopin in the 19th century must still be traveling somewhere through space. While I spent the best part of that lesson listening to him going off the deep end, I remember simultaneously thinking about his theory’s implications, and the potential horror of having every sound ever made still lingering around. Laws of physics aside, I did like the idea of music being eternal, its sound waves forever bouncing around waiting to be heard by new ears.

In that regard, Esbjörn Svensson’s last year’s album HOME.S. had to wait a long time to be heard by another pair of ears besides his own. Recorded just weeks before his life tragically got cut short in a diving accident in 2008, it was only recently that his wife Eva Svensson and sound engineer Åke Linton discovered its contents on backup hard drives. Esbjörn apparently recorded the album alone in the comfort of his own home studio over the course of that spring, leaving behind nine tracks worth of solo piano explorations.

The album’s tracks are posthumously titled after the first nine letters of the Greek alphabet, a symbolic nod to Esbjörn knowing the alphabet by heart due to his interest in astronomy (stars within a constellation are usually lettered from alpha to omega, roughly in order of brightness). In Christianity however, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet are idiomatically used to illustrate the comprehensiveness and eternity of God, proclaiming Himself to be the beginning and the end. Apropos this all-encompassing comprehensiveness, I can’t help but feel a similarity in scope upon listening to HOME.S., at least from a pianistic point of view. Throughout, it unfolds a lifetime of profound musical study, echoing his devotion not only to jazz, but also to the great classical composers to an extent only few can.

There is something deeply intimate and moving about hearing Esbjörn playing to no one but himself, in a room he probably spent a good part of his private life in. At the same time, it also feels strangely intrusive, considering the possibility that these recordings were never meant to leave his studio. In light of 19th century physics, we could consider it a tiny miracle these sound waves found a way into the world after all. Sound waves that were bouncing around waiting to be heard. Perhaps my piano teacher was right all along.

Esbjörn’s alternating pedal points

Although it remains debatable if the term ‘’Eurojazz’’ has any significance beyond the scope of American music criticism, there is something intrinsically un-American about Esbjörn’s approach to jazz. Especially in regards to his contrapuntal left hand, cadenza-like straight feel passages, and his approach to voicing harmonies, which all seems to stem more from the European classical tradition than the lineage of jazz. One of these musical devices can be heard throughout his oeuvre, including HOME.S.’s first track Alpha.

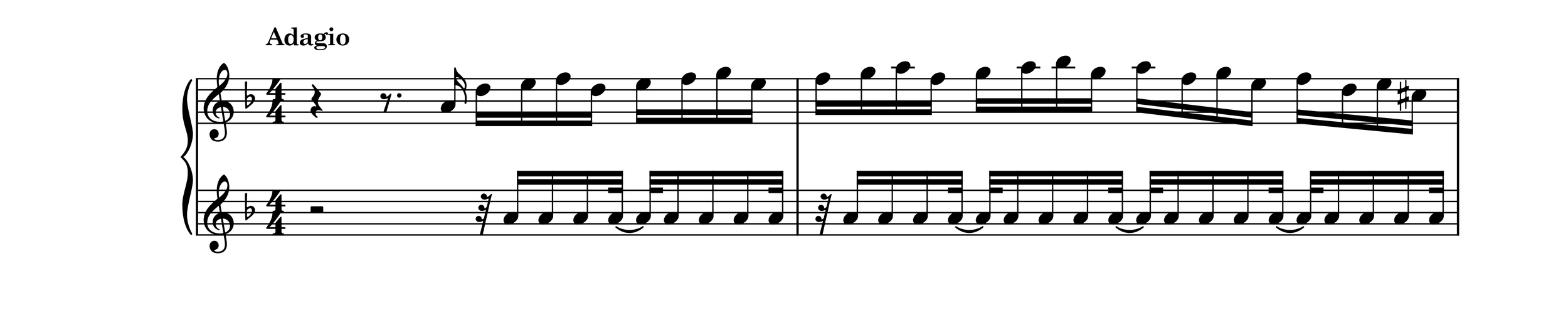

Excerpt from Alpha’s final act (3:09–3:50)

Highlighted in orange, rapid melodic oscillations are scattered throughout Alpha’s final act. Sounding not unlike a tremolo, this melodic figuration is explained as an alternating pedal point in John Mortensen’s The Pianist’s Guide to Historic Improvisation. Defined as a ‘’moving line alternating with a pedal tone’’, Mortensen states that this pedal tone is usually –but not limited to– a tonic or fifth, especially in 18th century music. In Schenkerian analysis, this device is also referred to as compound melody, since there is an implication of more than one melodic line by a single voice. Alternating Pedal Points can be found everywhere in the classical standard repertoire:

Mm. 12–13 of J.S. Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV. 565

Mm. 4–5 of Franz Liszt’s ‘‘La Campanella’’, from his Grandes études de Paganini, S.141

Being a staple of classical technique, the alternating pedal point can also be found in The Virtuoso Pianist by Hanon, serving perfectly as introductory exercises:

Exercise no. 6 from Hanon’s The Virtuoso Pianist

Exercise no. 31 from Hanon’s The Virtuoso Pianist

To create dazzling flourishes of sound, Svensson uses these alternating pedal points in conjunction with different melodic motifs, acting as modular cells that can be connected in any order to form longer phrases.

He uses alternating pedal points mostly to target chord tones from below:

Using alternating pedal points to target the root, third and fifth of C major

We can start building longer phrases by adding a second melodic motif preceding the alternating pedal point (note that our second melodic motif starts on the note above our target note, creating a diatonic enclosure):

Adding a second melodic motif preceding our alternating pedal point

A third preceding melodic motif is used to finish our own Svensson flourish. (the highest note of this motif is the highest in our whole phrase).

Finishing our Svensson flourish with a third melodic motif

Try to practice these 3 melodic motifs –by themselves and/or together– over your favorite jazz standards to familiarize yourself employing these flourishes in musical contexts. To add complexity and interest to your flourishes, try to permutate these 3 melodic cells, target different chord- or even non-chord tones, and add chromaticism or modal mixture like in the examples down below.

Adding complexity to your Svensson flourishes